'Une campagne ne se passe jamais comme prévu' - You never get the election you expected

The run-up to French presidential elections is always marked by a flurry of activity among publishers and politicians.

In the year or two before the election, candidates or would-be candidates, what the French call présidentiables, will publish works that put their ideas out there amongst the public – nothing too taxing mind and a nice big font size and all for around €20. Thus François Fillon’s Faire (Essais-Doc, 2015), Natalie Koscziusko-Morizet’s Nous avons changé de monde (Albin Michel, 2016), Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s collaboration with Marc Endeweld on Le Choix de l’insoumission (Seuil 2016) or Emmanuel Macron’s Révolution (XO, 2016), to name but a few. Among the candidates for the candidature, I think the record this time goes to Alain Juppé, who produced no fewer than four books to bolster his campaign for the right-wing primary. And look where that got him. Often, of course these books are not produced by politicians themselves, but by their advisors and collaborators, but you get the point.

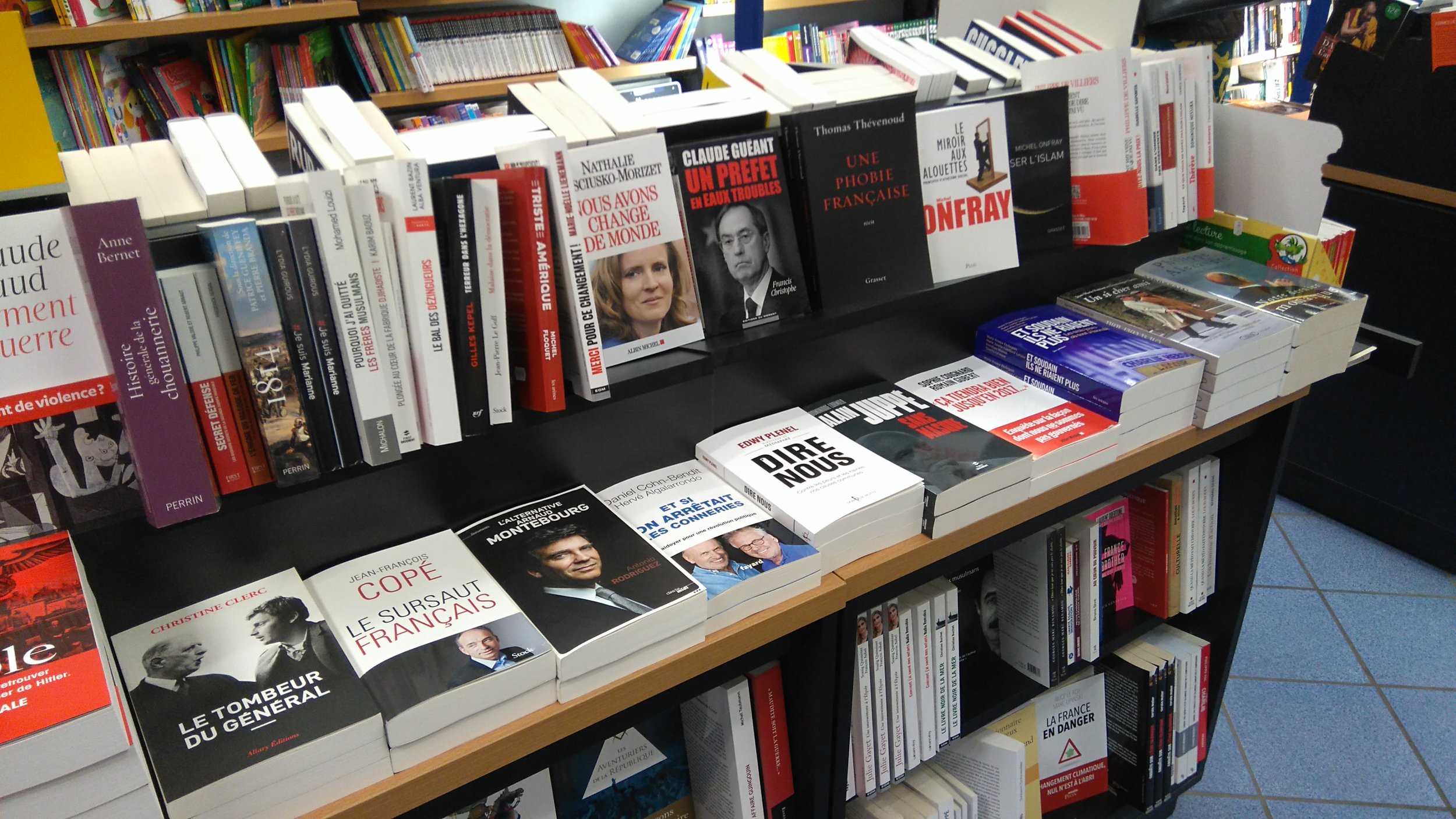

Spring 2016 and those pamphlets are flying off the shelves in Bretenoux (46)

Less prolific in this regard, Marine Le Pen, has not produced any work herself since Pour que vive la France (Jacques Grancher), published in February 2012. Instead, there is a huge literature about her and the workings of the Front National produced either by journalists or academics or both. So, just as she complains about not getting much media exposure (while in fact getting a disproportionate amount compared to some other figures), there is also a very fertile field of FN publishing.

An unlikely vision of Marine Le Pen welcoming migrants who have risked life and limb to cross the Med .

Le Pen is more often the subject of ‘fast book’ biographies of candidates. The best example of one of these this time was Anne Fulda’s Emmanuel Macron – un jeune homme si parfait (Plon, 2017). Fulda, who made her reputation mostly working for the right-wing Le Figaro, has also produced a similar study of François Baroin in the past (JC Lattès, 2012). Clearly, she likes to work on the good looking lads.

Le beau gosse...

While books or pamphlets (because that’s what they really are) by présidentiables represent one side of the trade, on the other are the works of academics and journalists, produced to remind the French about past campaigns either over the longue or courte durée. The title of Christophe Barbier's Deux présidents pour rien 2007-2017 tells you pretty much where he's going with that. A more weighty bookand one I’ve been ploughing through is Parties de campagne. La saga des élections présidentielles (Perrin, 2017), by Gérard Courtois, who has been political correspondent and editorialist for Le Monde for more than thirty years.

The title is a play on words. Une partie de campagne is a day in the countryside, and the word une partie with an ‘e’ on the end has nothing to do with un parti. But the word campagne can mean campaign as well as countryside. And while we are on today’s vocabulary note, une partie can also mean a game of… Thus une partie d’échecs means a game of chess, whereas un jeu d’échec is a chess set and un jeu de cartes is a pack of cards. So, it's a game...

Courtois is not everyone’s cup of tea, but he is one of the few journalists who puts his hands up and admits to his mistakes. In an editorial in Le Monde on 27 April 2017, he admitted to making three ‘mécomptes’ or miscalculations in the run up to the first round.

The first was underestimating Macron and believing, as many others did, he would be undone because he had not followed the political cursus honorum, either in local politics or in a party and preferably both, and that he did not have an organised party behind him. Well, we all felt that. How many times was En Marche! disparagingly referred to as looking like ‘un start-up’?

Secondly Courtois was spooked by a poll that suggested Le Pen would not only win the first round, but that she would take more than 30% of the vote, setting her well on the way to a win. He also expected her to be better on the campaign trail. We all did.

Thirdly, Courtois fell for Fillon’s insistence, in the last fortnight before electors went to the polls, and as Penelopegate faded into the background, that he would actually pull it out of the bag. There was some reason to believe this might happen. After all, the right had taken 28% of the national vote in the regional elections in December 2015 and won 17 of the 20 by-elections to the National Assembly since 2012. Surely the right-wing electorate was still out there?

Penses-tu, François...

Fair play to Courtois for the mea culpa, but we were all wrong-footed and, as he himself stresses in the first chapter of Parties de campagne, ‘Une campagne ne se passe jamais comme prévu’ – You never get the campaign you’re expecting.

So what were we expecting from the 2017 presidential election?

In the first place, we expected Les Républicains to win. Not simply because we were all still stuck in a right-left paradigm (!), though that was part of it, but because they seemed to have candidates to do it. The 2012 election was as much an anti-Sarkozy referendum as an endorsement of Hollande and once he had gone and even despite the bitter in-fighting between Fillon and Jean-François Copé to seize control of what was then the UMP, the re-emergence of Alain Juppé appeared to offer a moderate right-wing solution.

Sarkozy’s return to head the UMP and change its name to Les Républicains destabilised his opponents momentarily, but the insistence on a broad primary, beyond the party membership, a condition that all his opponents agreed on, undermined the former President’s position. Still we all thought, even up until the last minute, that the contest was between Juppé and Sarkozy and that Fillon, if he performed well, might play the kingmaker.

In the summer of 2016, the best guesses were that Juppé was the candidate best placed to rally left-wing support in a run-off against Le Pen. No-one thought the left could find a candidate to challenge her, nor did we think Hollande would stand again. Juppé’s problem was trying to persuade right-wing voters that he was a man of the right, not the left. In some ways, he was always fighting the next election. The other problem, as Gilles Boyer points out in his very readable account of Juppé’s comeback, was that he was too high in the polls too soon (Rase Campagne – JC Lattès, 2017) and electors get bored.

So, we expected a Juppé-Sarkozy contest and all the polls pointed that way. But primaries are profoundly unpredictable and the electorate volatile. Like Juppé, Fillon played the long game, but was able to avoid the spotlight and to build his popularity out in the constituency party and among the local electorate, despite Sarkozy’s return. And we know the outcome of that. Juppé and Sarkozy were so obsessed with one another that they overlooked the former prime minister.

Fillon became favourite to be the eighth president of the Fifth Republic, but there was a problem. Branded ‘the French Thatcher’, promising austerity and cuts in public services to the tune of 500,000 posts, and happily getting cosy with traditionalist Catholic groups that had come out of the woodwork over same-sex marriage, adoption and surrogacy, his policies and his rhetoric looked antagonistic. Not only to the ‘soft’ right, but also to left-wing voters who would be called to vote for him if he went through to the second round against Le Pen. Fillon in 2017 certainly wasn’t Chirac in… well, ever.

December saw support for Fillon begin to slip a little and just as he was preparing his big return, at the end of January, Le Canard enchaîné published revelations about his wife’s fake job as his parliamentary assistant. Fillon appeared on television with, hand on heart, a promise to stand down if he was formally charged. He also announced that he had employed two of his children as assistants when he was a senator. The press hadn’t even got that far, but they had a field day.

Fillon shot down the polls and never fully recovered. His programme, combining austerity with strong rhetoric on immigration and identity was drowned out by the controversy around whether he would even stand in the first round.

We had expected immigration and identity to be key themes of the election, but neither Fillon nor Le Pen really managed to make them stick and the discourse of the ‘choc de civilisations’ got lost behind issues of transparency, not just around Fillon, but also Le Pen herself. Her ‘tous pourris’ and ‘tête haute, mains propres’ slogans – 'All (politicians) are rotten' and 'head held high and clean hands' – looked rather doubtful when revelations began to come out about FN finances and the misuse of funds from the European Parliament to pay party workers.

Le Pen had announced her intention to stand in the spring of 2016, but took most of the year off, until the rentrée politique in the autumn. If the sabbatical was intended to allow Le Pen to recharge her batteries, it didn’t work. She remained oddly lethargic from the outset and failed to force the debate into the areas she was strongest. At every turn the campaign slipped beyond her. In part she was a victim of the Fillon Affair, because it also shone a light on her party’s problems. She failed to make any real impact in the televised debates before the first round and then, having qualified for the second, simply spent the face-to-face with Macron wearing that grin of insolent disbelief that she does, falling over her own policies and failing to land a single blow on Macron.

Her fate had been sealed before then. Le Pen’s first round score was poor. Everyone expected her to get through to the second, but most commentators expected her to be in first place. Her position and her score were disappointing. And but for Nicolas Dupont-Aignan taking votes from Fillon, she wouldn’t have made it at all.

So you can add Dupont-Aignan nearly getting to the 5% threshold as another unexpected aspect of the election, as well as his willingness to appear, between rounds, with Le Pen as her putative PM. The consequences for his own Debout la France party were enormous and he very nearly didn’t get back into parliament in the general election as a consequence.

What of the left? I have already said that we didn’t expect Hollande to stand. There was a great deal of frustration among his opponents that he didn’t stand and defend his record, but what would have been the point? His thunder had been stolen by Macron and, in late November, Manuel Valls.

I don’t think anyone thought Valls would win the left-wing primary. That election was fought in a spirit of ‘tout sauf lui’ (anyone but him - meaning Valls) just as much of the right-wing primary was all about beating Sarkozy. But we expected Valls and Arnaud Montebourg in the second round, not Valls and Benoît Hamon. The latter’s victory was probably fatal for any vestigial hope the PS had of rescuing something from the wreckage of Hollandisme. Montebourg might have made a bigger dent in both Macron and Mélenchon. In any case, I think if you had taken a punt in the autumn of 2016 on Hamon as the PS candidate, you’d have got very good odds.

Mélenchon was a surprise too. Apart from appearing in two places at once, via hologram technology, and managing not to start a fight with himself, the former senator for the Essonne focussed on his own programme (probably the only truly ecologist programme of the campaign) rather than making Le Pen’s life unbearable, as he had done in 2012. Back then, when France first caught mélenchonite (Mélenchonitis), he had risen as high as 14% in the polls. He himself had reined in his campaign so as not to scare moderates who might vote Hollande, and finished on 11%. Defeating Sarkozy was more important, but he regretted it.

In the immediate aftermath of Hamon’s winning the left-wing primary (in which Mélenchon refused to take part), Hamon surged past him in the opinion polls, But Hamon then wasted a month negotiating with the Green candidate Yannick Jadot, who withdrew in Hamon’s favour. Mélenchon would not be drawn into an alliance and it paid off. Little by little he gnawed into Hamon’s support, to the point that, as the weekend of the first round approached, he truly believed he would be in the second round. Hamon’s mistake was that he failed to mobilise what was left of the party behind him, preferring to keep his campaign meetings to a tight group of collaborators who had been with him in the Young Socialist movement. And his programme was poor.

The 2012 campaign clearly hadn’t inoculated France against Mélenchonitis and on the eve of the first round, the founder of La France Insoumise (who declared himself a candidate fully a year before the election) believed he would get through.

In the course of the evening of 23 April, his representatives cut very aggressive figures as they did the rounds of the TV plateaux and refused to accept the exit poll figures being used by the media that saw their candidate eliminated. But what seemed like bad grace then in fact had a sound basis.

French polling stations close at 6 in the evening, or 8 in the larger urban centres. The early exit polls used on the 8 o’clock news tend to come, then, from the smaller communes and towns and it’s only later on that the figures from the big cities are factored in. This explains how, on TF1 for example, Macron and Le Pen were level pegging when the results were first announced, but Le Pen soon dropped back, because, on the whole, she does badly in France’s big cities.

Mélenchon does well there though and he was waiting on the results in the urban centres to come in before accepting the result. In the end, the final opinion polls and the exit polls used on France 2 (though not TF1) were more or less correct. But the result was tight enough for Mélenchon to want to hold fire, albeit grumpily.

Courtois reminds his readers that François Mitterrand once said that to win the presidential election, you need three things: a candidate who knows how to campaign; a party ready to march (‘en ordre de marche’); and a programme or at least three or four key measures that everyone can grasp (page 13 if you’re looking). Edouard Balladur, a losing candidate in 1995, once said that if you don’t think about the presidency every day, you’ll never be president.

Despite what looked, at the time, to be enormous disadvantages before him when he announced his decision to stand in the spring of 2016, Emmanuel Macron managed to draw all these things together. His campaign might not have set the world alight, but he handled himself better than everyone else. He struggled to keep himself in check in the debate with Le Pen on 4 May, but she hit the self-destruct button at the outset. And his programme was clear enough to appeal to voters and, an element that has been overlooked, local militants from centre-left to centre-right.

In the course of the campaign, I was invited by a number of media outlets to comment on whether Macron could win without a party behind him. We all missed the point. He had a party that absolutely conformed to Mitterrand’s definition and was committed to one thing – putting Macron in the Elysée. I mentioned above a rather disparaging attitude to En Marche!, but no-one can deny it worked. A convention at La Villette on 8 July will finally adopt a 'roadmap' for this party that is not yet one.

Of Macron’s main rivals, perhaps only Mélenchon had all three strings to his bow. Fillon was never able to show if he was a decent campaigner and the party soon did what it does best. Le Pen tried to control the FN in the same way as Macron, but not everyone in the party was convinced of the line she and Florian Philippot decided to take. If her niece, the party poster-girl Marion Maréchal Le Pen was largely sidelined during the campaign, it was for a reason. And I still don’t think Le Pen fulfilled the first criterion. Did she really want the job and does she still?