Erreur de Castex? Astonishment and bad puns as Macron names his new PM

France’s new PM Jean Castex

Read MoreFifth-and-a-half Republic is a blog about contemporary French politics by Paul Smith, Associate Professor in French at the University of Nottingham.

France’s new PM Jean Castex

Read MoreMarseille has a new maire - Michèle Rubirola of Printemps Marseillais

Read MoreMartine Vassal, LR tête de liste in Marseille, and the retiring mayor Jean-Claude Gaudin

Read MoreGrégory Doucet, the new mayor of Lyon

Read MoreAnne Hidalgo, centre, leads the charge for the Hôtel de Ville

Read MorePrime Minister Edouard Philippe, mayoral candidate for Le Havre, looking relaxed

Read MoreIs Emmanuel Macron really planning to show Edouard Philippe the door?

Read MoreSex doesn’t always sell - Bruno Louis’s list managed only 3.8% of the vote

Read MoreThe colours of déconfinement

Read MoreA colour-coded déconfinement

Read MoreEdouard Philippe at the National Assembly - 28 April 2020

Read MoreAnne Hidalgo - looking good for Paris

Read More

2014’s French municipal elections showing the results for larger communes

So, despite announcing to a TV, radio and online audience of nearly 25 million on Thursday evening a raft of measures to combat the coronavirus COVID-19, Emmanuel Macron has decided that the municipal elections in the 34,968 communes of mainland and overseas France will go ahead on 15 and 22 March. Before his address, there had been speculation that they might be put back, but according to various sources, leaders of the moderate right, including the speaker of the Senate (Gérard Larcher) and the chair of Association des Maires de France (François Beau-Gosse Baroin) made forceful objections. (A suggestion that Laurent Fabius, chair of the Constitutional Council also had a hand in changing Macron’s mind was denied via the Council’s Twitter account on 13 March.) Quite what the turnout will be is an altogether different issue with so much other background noise over the last few weeks making it difficult for voters to hear the campaign going on.

Municipal elections matter to the French. My rule of thumb when talking about them to my students is that, while in Britain the overall turnout is about 30%, in France that is the general abstention rate. Well, okay, in the big cities turnout is around 55-60%. In rural communes, the turnout (taux de participation) can be considerably higher. In La Chapelle-aux-Saints, an agreeable and rather dispersed village on the edge of the Corrèze and the Lot where Fifth and a Half happens to have a modest abode, the turnout among the 211 électeurs in 2014 was 86%. The term commune, by the way, has nothing to do with tree-hugging hippy **** nor with radical left-wing politics or any of that sort of malarkey. It is simply the smallest unit of local government in France, although some communes are much bigger than others. Basically, when the French Revolutionaries were redrawing the administrative map of France, they used the old parishes as the lowest level of jurisdiction, shifted a few boundaries here and there and relabelled them as communes. The adjective that is used to describe their election, however, is municipales and not communales. So now you know.

In this blog I’ll explain how the elections work. I’ll look at the political stakes in a later post.

Each commune has a local council whose size is determined by its population, on a sliding scale outlined below.

Altogether, the process will involve the election of more than half a million councillors, but there are two methods of election. In communes of up to 1,000 inhabitants, election is by majority system where candidates can stand on a list or indidividually. The lists are not, however, blocked, and voters can express their preference for candidates from different lists or for individuals. If the requisite number of councillors obtain more than 50% of the vote in the first round, there is no run-off, but if any seats remain to be elected - by no means an unsual situation - voters are summoned to fill the remaining seats a week later.

In communes of 1,000 inhabitants or more, a system that looks like PR is used, but don’t let that fool you. In reality, it is a majority list system with a dose of proportional representation: the list that wins, whether they get an absolute majority in the first round or a relative one in the second, is awarded half the seats on the council. Only then are the remaining seats shared out among all the lists, using the D’Hondt method of the highest remaining average and on condition that they receive 5% of the votes cast. If no list wins an absolute majority in the first round (and that’s the norm given the fragmented nature of French politics), then any list that gained 10% in the first round can stay in the race, while candidates on lists that gained at least 5% of the vote can merge with others. (In these communes, the rules on parity apply, so the lists must alternate between female and male candidates or vice versa, depending on who is the tête de liste. This is not the case in the smaller communes.)

By way of a very rapid illustration, the table below shows how the system played out in Nice in 2014, where eight lists from the first round were reduced to four in the second, competing for 69 seats on the municipal council. Christian Estrosi’s right-wing Union de la Droite list (aka Ensemble pour Nice) had taken 45% of the vote in the first round and increased its share to a shade under 49% in the second. But as the table shows, the consequence of the system was that the ruling group took 52 seats on the city council and 49 on the conseil communautaire serving the ‘greater Nice’ area.

These are the general rules that apply to all 34,968 - or at rather 34,862 - there are 106 were there are no candidates standing, which means the departmental prefect’s office has to step in and administer the commune. There are three exceptions. Lyon, Marseille, and Paris are subdivided into arrondissements or secteurs and councillors are elected at the same time for these district councils as well as the overarching city councils. In Paris, for the first time, the central 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th arrondissements will operate as a single electoral district and elect a single council, the other 16 will continue as before.

Meanwhile, down in Lyon, something new will be happeneing. Voters in the ancient ‘Capital of the Three Gauls’ will vote for their arrondissement councillors, and a portion of these will sit on the city council, the number depending on the population of their district. But voters in Lyon and 58 other surrounding communes will be casting a second vote for the new metropolitan council of ‘le Grand Lyon’ - greater Lyon.

Oh, and on account of Brexit, nearly 600 British nationals who sat on various outgoing municipal councils will not be able to stand again…

A suivre…

Marion Maréchal just couldn’t let her aunt enjoy the moment…

Read MoreThe fall of Laurent Wauquiez was an accident waiting to happen. But has the ‘stupidest right in the world’ learned any lessons?

Read MoreI’ll be honest. I was not all that optimistic about the turnout ahead of Sunday’s European elections in France. This year, 26 May marked the Fête des Mères and I had visions of carloads of French voters heading off to chez jolie-maman, via the boulangerie to pick up dessert rather than the polling station. Ahead of the election, opinion polls were predicting a better-than-normal turnout – something of the order of 45%. On Friday evening, pretty much the last sondage was suggesting 47%. Imagine everyone’s delight, then, when at lunchtime, French radio stations and news channels were suggesting a turnout that pointed towards above 50%. Whatever one might think about French disaffection with mainstream politics (as opposed to the gilets jaunes), clearly half the pays légal thought it worth their while to drop into the mairie to pop their envelope in the perspex box.

In the end, the taux de participation was just a shade over 50%. How does this compare with previous European elections? Pretty well. My ‘go-to’ for election statistics is the france-politique website maintained by Laurent de Boissieu, journalist with La Croix and a commentator whose Twitter feed is also worth following. The figures can be found here. The first European elections in 1979 saw a 61% turnout. This dropped to 57% in 1984, 49% in 1989, rose to 53% in 1994 before dropping down to 47% in 1999, 43% in 2004, 41% in 2009, before a small rise to 42% in 2014. An hour before the first estimates of the results arrived, we were told to look out for 52% turnout. In the end, it was 50.12% nationally. How might we explain this?

There are a number of factors. The gilets jaunes movement is certainly one of them. While the yellow vest lists did poorly - most voters who identified themselves as supporters and who said they would vote, indicated that they would vote for more ‘conventional’ list – the social crisis has had an impact.

Climate change politics also has clearly had an effect – the late surge by Les Verts, which I’ll come back to in a moment, lifted the turnout.

There is also something to be said for the form and the timing of the election. By the hazards of the electoral calendar, this is the first electoral test for Emmanuel Macron. European elections always fall two years after the presidential elections, but his two immediate predecessors - Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012) and François Hollande (2012-2017) - both had to negotiate nationwide municipal elections before the European ones. Sarkozy had not been in office a year before the French told him what they thought of the Président Bling-Bling in les municipales in March 2008. And while le Président Normal had a little longer to prepare, the same happened in March 2014, a couple of months before the European elections. Both were used by the electorate as votes sanctions against the President. (And if you think municipal elections do not matter in France, you really have a great deal to learn.) So, as a first test, the Macron list and his ‘pop-up’ party did reasonably well.

The final factor is the return to a national vote. In 2004, 2009 and 2014, the French used a system of super-regions, not unlike the British system, but unique to European elections. The system was introduced in 2003 by the then PM Jean-Pierre Raffarin and interior minister Sarkozy as a means of damage limitation for Jacques Chirac’s presidential Union pour un Mouvement Populaire, although it failed in that regard. And, on the whole, ruling majorities do not do well in European elections. By my reckoning, the ruling parliamentary party or coalition (NOT the presidential party) has only ‘won’ the European elections on four occasions (1979, 1994, 1999 and 2009). And even then, the results have to be unpacked a little… another time.

The rate of participation/abstention was not the same everywhere, however, and there were some very wide differences in metropolitan France, ranging from a low of 40.8% of abstention to nearly 62% in Corsica and nearly 60.5% in the Paris suburban department of Seine-Saint-Denis. (The official results by department can be found on the Interior Ministry site here.) (In overseas France, the rates of abstention were considerably higher.)

Figure 1 - Le Monde, 28 May 2019

So much for the turnout, Paul. What about the results? Well, here’s a graphic from Le Parisien:

Figure 2 - There were 34 lists - these are the ones that secured more than 1% of the vote. Lists over 3% are eligible for reimbursement of their election costs, but only those over 5% get seats.

The campaign had hardly set the electorate on fire. In the context of the yellow vests movement, the Grand Débat National and Macron’s proposals in response to that, the elections had really taken a back seat until the last couple of weeks, when it became clear that both Marine Le Pen and Emmanuel Macron were going to reduce/elevate the process to a duel between them and their two parties. In that respect, the election turned out as we expected, with Le Pen’s rebranded Rassemblement National-led list winning the largest share of the vote, at 23.3%. Unlike 2014, when she had no national seat in parliament and therefore headed the campaign, Le Pen was not up for election, but installed as tête de liste her new protégé, the 23 year-old Jordan Bardella.

The choice of Bardella was very much hers, and so, in terms of the internal dynamics of the RN as well as national politics, it was important for the list to finish in first place. Mission accomplished then. Finishing second to the Macron list would have been a serious blow to Le Pen, given the wider context of social discontent and doubts within her movement of her ability to win an election in the wake of 2017. Bardella’s youth also points to a young figure being groomed for the succession and challenge to the lurking presence of Marion Maréchal in the background. Domestically, then, the result has shored up Le Pen’s position within the party as well as establishing her and the RN as THE opposition to Macron.

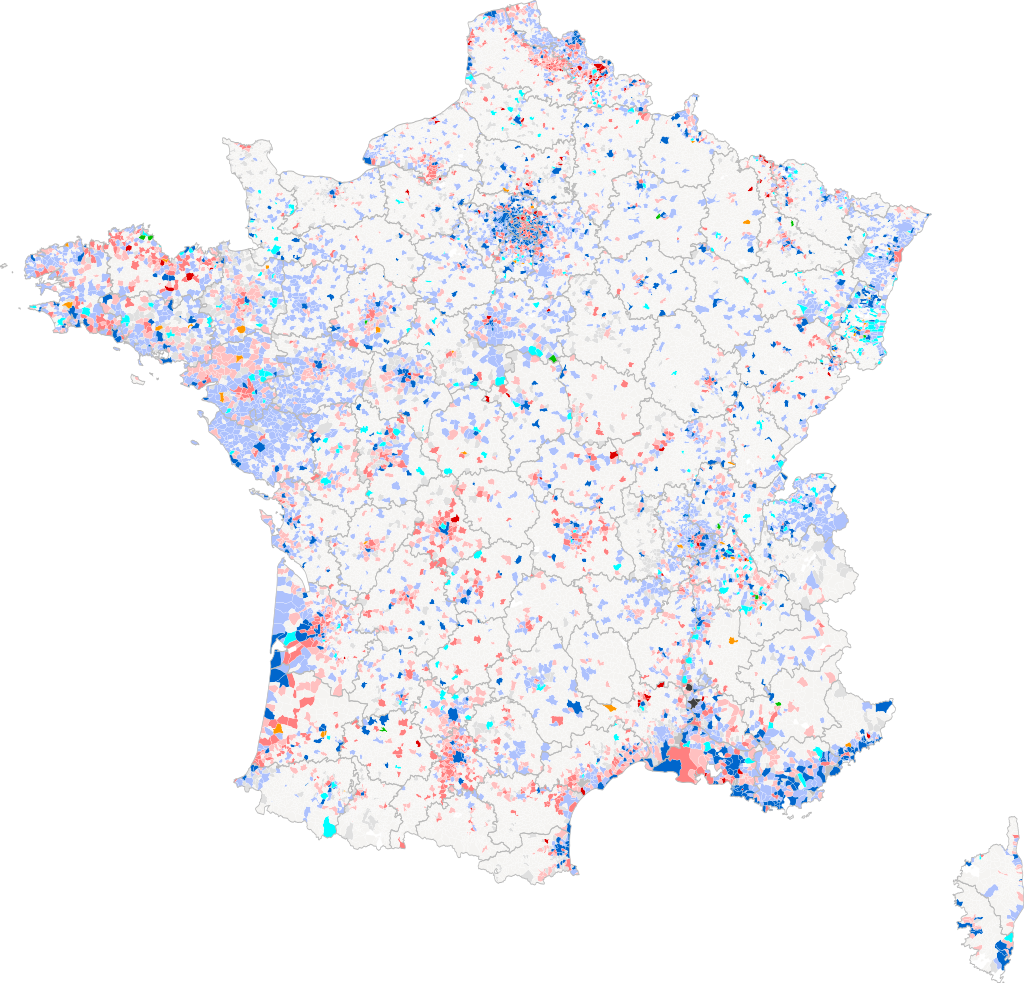

And therein lies the rub. Since the results were announced, various commentators have taken the line, in France and across Europe in general that ‘the far-right populists didn’t do was well as expected’. Perhaps not. But they are now a feature of mainstream politics, not the periphery. Thus, while we can point out that Le Pen’s FN/RN did better in the 2014 European elections (first with 25% of the national vote) and in the 2015 regional elections (first again nationally with 28% of the vote), this result shows that the French far-right have consolidated their position geographically. This is not just a party getting huge votes in certain areas - see Figure 3 below. It is, moreover, a party that mobilises its troops. Something like 80% of those who voted for Le Pen in 2017 turned out to vote, compared to only 54% of macronistes and barely one-third of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s voters from 2017. (In figure 3 below, communes that voted RN are in pink, LREM in orange. This is a little confusing, because traditionally pink is the colour of the left-wing PS, but that’s Le Figaro for you. Le Monde uses brown…)

Figure 3 - the results by commune from Le Figaro - don’t you just love GIS electoral mapping software?

It’s unusual for a President to get quite as involved in a secondary election as Macron did, but the situation is unusual, and it should not be forgotten that La République en Marche (LREM) remains a work in progress. The wider political context forced his hand and it became inevitable when he launched the Grand Débat and became heavily (perhaps too heavily) implicated in that. His choice of Nathalie Loiseau, the European affairs minister, as tête de liste may or may not have been a good one. She didn’t perform terribly well in the pre-elections debates, but she was by no means the worst. The opinion polls had the LREM and their allies more or less neck and neck with the RN until the last ten days or so, when the RN crept ahead. It’s always risky turning an election into a plebiscite, but Macron had very little choice. In the event, the result was better than it might have been. However, as PM Edouard Philippe said on Sunday evening, ‘if you come second, you haven’t won’. (Wise words, Ed.)

It was the results behind LREM that were the shocks and, in a sense, a pleasant surprise for Macron (and to some extent Le Pen). Paris Match’s survey of opinion polls had third place going to the maintsream right-wing party, Les Républicains (LR), credited with 14% of voting intentions. That had been the ball-park figure throughout the campaign and at party headquarters on the Rue Vaugirard there was a general feeling that, as with the Fillon campaign in 2017, a late tailwind might even push the list, headed by François-Xavier Bellamy, through the 15% barrier. There was general consternation, when the first exit polls released at 8.00 pm put them in fourth with less than 9% and that is where they stayed. So much, then, for the party that, in late 2016, was a shoo-in for the Elysée.

Just as these elections were always going to be a stern test for the new LREM, just so they would be for the president of LR, Laurent Wauquiez. Elected at the end of 2017 (see my blog entry for 14 December 2017), the president of the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region has been heavily criticised from within his party for taking the LR down the path of identity politics, stigmatised by the wonderfully sardonic Edouard Philippe as the droite Trocadéro. Wauquiez chose Bellamy as tête de liste as a copy of himself (on Bellamy see Arthur Goldhammer’s excellent comment here) rather than a leader who would reach out across the famille de la droite et du centre, but in truth the family needs to take a long hard look at itself. Although LR has 100 deputies in the National Assembly and controls the Senate, the party has still not come to terms with its response to Macron and on Sunday that showed, as disaffected centre-right voters supported the LREM list and not Bellamy.

Wauquiez’s critics within LR, particularly Valérie Pécresse, president of the Ile-de-France region and Gérard Larcher, speaker of the Senate, wre not slow to voice their views. In the opinion of the former, Wauquiez had no option but to resign. If Larcher, by virtue of his office the deuxième personnage de la République was marginally more circumspect in public, in private he has echoed Pécresse and, using his position as speaker has begun to try to rally the right and centre-right ahead of next year’s now critical municipal elections. Apart from its homelands in the Massif Central the LR electorate was virtually invisible and many of its voters simply stayed at home, especially in eastern and south-eastern France. Don’t let Figure 4 below fool you. The scores in departments like the Alpes-Maritimes (Nice) were appalling.

Figure 4 - Le Monde, 28 May 2019

Les Républicains switched places with Les Verts (EELV), the Greens, led by Yannick Jadot. Credited with perhaps 8-9% of the vote by almost every opinion poll, they were boosted by a last minute vote (according to reports 25% of EELV voters decided to vote Green at the very last minute). But let’s not get ahead of ourselves here. While ecology is undoubtedly part of the zeitgeist, we have been here before. I can remember the 1989 election, when the Greens made their ‘breakthrough’ with 11%, only to then slip away in 1994. In 2009, they took 16.28% of the vote, just behind their future allies the PS. It was on the basis of those results that François Hollande promised them seats in the National Assembly, brought them into his electoral coalition in 2012 and they responded by running a very poor candidate, Eva Joly (fine person, poor candidate). In 2014 and out of government they slipped back below 9%. And in 2017, Jadot (very foolishly) stood down in favour of the doomed PS presidential candidate Benoît Hamon. Jadot’s success is in part thanks to the failings of the moderate left, but also to disaffection among ecologist voters with Macron, disappointed by the limitations of his policy, embodied by the resignation of environment minister Nicolas ‘sort of the French David Attenborough’ Hulot late last summer.

Figure 5 - Allez les Verts… until next time. Le Monde 28 May 2019

It’s worth noting the strength of the Green in Brittany the Alps and the southern Massif Central, as well as, for the first time ever, Corsica, where Jadot’s list polled 22%, behind the RN on 27.7%, but well ahead of LREM on 15%, a reflection of what Corsicans see as Macron’s high-handed attitude to their ‘sensibilities’.

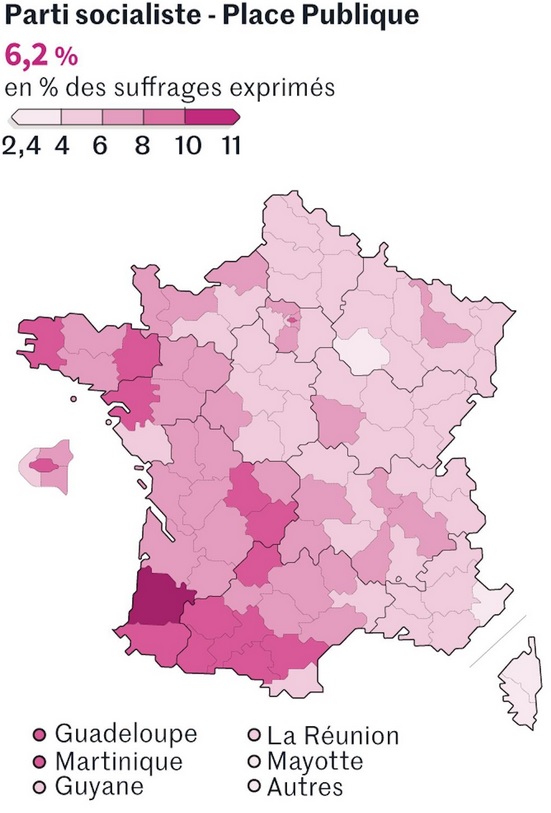

In France, the Greens are generally considered to be on the left, and their success is in some way accounted for not just by dissaffection on the left of the LREM (some 17% of EELV voters on Sunday voted Macron in the first round in 2017) but also frustration with Hamon, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (from 19% to 6.3% for heaven’s sake), and to a lesser degree with the Parti Socialiste. Of these, at least the latter, led by Raphaël Glucksmann (PS-PP), held on to the same proportion of the vote as its candidate (Hamon) did in 2017, while Hamon managed a shade over 3% and at least gets his election expenses reimbursed. As Figure 6 below shows, the PS can still count on its Breton and south-western heartlands. (Raphaël Glucksmann is a philosopher who set up Place Publique as a pro-European centre-left party outside the PS but also to counter the influence of Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise.)

Figure 6 - La gauche cassoulet is alive - Le Monde, 28 May 2019.

Over-optimistic French left-wingers picking over the results were excited to point out that if one added Jadot, Glucksmann and Hamon’s voters together, they would be neck and neck with Loiseau. And if one could persuade La France Insoumise (LFI - led in the election by Manon Aubry) plus the Communist Ian Brossat to join, then that took them past the 30% marker. But that sort of wishful thinking has no basis in political reality.

Where did it go wrong for Jean-Luc Mélenchon and the insoumis? Surely the natural party of the gilet jaunes, instead it seems that, if the yellow vests voted for any party in particular, it was the Rassemblement National. From 19% in the first round of the presidential election in 2017 to less than one-third of that score in 2019. Within the party, patience has begun to run out, not least on the part of deputy Clementine Autain, exasperated with Mélenchon’s ‘anti-everything’ approach, which seems to boil down to shouting at everyone (my view, not Autain’s).

Figure 7 - LFI - Big in the Ariège, Seine-Saint-Denis and overseas… anorexic everywhere else Le Monde, 28 May 2019

One of Autain’s criticisms of Mélenchon has been the failure, justement, to create an alliance populaire of left-wing parties to challenge both Macron and also Le Pen. And it is true that it is the RN that has strengthened its support among working class voters. But continued weakness of the left offers some hope to Macron.

Macron the candidate, it will be remembered, emerged from the left. Macron the president, on the other hand, has governed, for the most part, from the centre and right. Without going into a discussion of policy we can see this simply by looking at the key ministries occupied by Philippe, Bruno Le Maire (finance) and Jean-Michel Blanquer (education). Sunday’s results to the left of LREM, however, offer Macron an opportunity not so much to shift to the left as to open up the possibilities of a group or even a party of centre-left macroncompatibles to mirror the Agir group in the National Assembly on the right of LREM and Modem and acting as a passerelle for disaffected members of LR. It won’t be easy, but it could well be a feature of Acte II of Macron’s presidency, particularly if he is capable of ‘greening’ his politics.

But one thing is certain in the wake of Sunday’s elections. The old left-right division of French politics is done. The division is now between progressistes et nationalistes if you are Macron and mondialistes et patriotes if you are Le Pen. On 12 June Edouard Philippe will outline the next phase of his government’s work to the National Assembly, ahead of a vote of confidence, thus formally launching the second phase of Macron’s presidency. Meanwhile the parties and politicians will look ahead to and begin to prepare the ground (if they haven’t already) for next year’s municipal elections, which one commentator has described as the ‘most depoliticised’ (apologies for the appalling Gallicism) of the Fifth Republic.That’s not quite true, in fact. Bipolarisation only really hit French local elections in the 1970s. Still… the transformation of the political landscape and other less obvious factors, such as the end of the cumul des mandats, have made local politics a fractured field. A gilet jaune mayor anyone?

If it looks like the Front National and sounds like the Front National…

I know it’s been a while, but I’ll plead the headaches. Events at Lille over the weekend of 10-11 March have, however, given me both a theme and a flow.

So, the weekend marked the Front National’s congrès de refondation, the culmination of (it says here) a period of reflection on the 2017 presidential and legislative campaigns, a broad and deep consultation of the membership on a range of issues the leadership deem central to the party and, as the principal tease, the promise of a change of name for the party.

To recap briefly: Marine Le Pen expected to go through to the 2017 presidential election run-off in first place. She finished second, behind Emmanuel macron and not very far ahead of François Fillon. Then, she expected to get 40% of the vote in the second round, but after a poor inter-round campaign and a disastrous head-to-head debate with Macron, she took just 34%. In the general election that followed, the party took just eight seats, and even one of them has defected since. In any other party, Le Pen would be toast, but populist far-right parties don’t behave like mainstream parties and this one is built around a dynasty. Instead, Le Pen jettisoned her main strategist, Florian Philippot, éminence not all that grise of the process of dédiabolisation (detoxification of the party image) last autumn and embarked on a process of ‘consultation’ of the grass roots, or whatever is left of them.

According to Le Canard enchaîné (24 January 2018), membership, and more specifically party subs, have taken a nosedive, which makes the recent ruling that banks should not refuse loans to the FN even more of a relief to the party. Now, that’s not so surprising. I have already commented on the rapid decline in membership numbers for LRM and LFI, as well as the participation rate in the LR presidential elections in December 2017. And it will also be interesting to see how many of the Socialists remaining 100,000 members actually vote in their leadership election this week. The bottom line is that parties always suffer in post-election periods. Still, the palmipède, as Le Canard enchaîné is also known, reported that in some departments the rate of subscription has dropped by 20-30%, while in Moselle, in the east of France, it is down 80%.

And so the Front National arrived in Lille, promising ‘un Front nouveau’ and selling coffee mugs with a compass pointing north-east, or possibly far-right, and bearing the words ‘I was there’…

Yes, but who in France uses a mug?

Now, while everyone loves a bit of merch, the party faithful might have been hoping for more than just another bit of crockery to put at the back of the cupboard, next to the Hénin-Beaumont Half-Marathon finishers mug. Most of the Saturday session had been set aside for unpacking the views of the membership of key questions, until Le Pen unveiled a surprise guest, none other than Time Magazine’s Scruff of the Year, Steve Bannon. (Okay, the scruff of the year bit isn't true.) His appearance was undoubtedly a coup and galvanised the congress while deflecting attention away from a lack of new ideas coming out of the refondation. (More of a dusting off of old ideas, reckoned Le Monde.)

Bannon was able to attend because he had come over to Europe to cover the Italian general election on 4 March and to make contact with the leaders of what he describes as an international network of national populist parties. Anyone else get the paradox of an ‘international network of national populist parties’? During the week, he addressed a meeting of the Swiss populist UDC in Zurich and also met the leaders of the German AfD.

Bannon’s appearance at Lille was organised through Le Pen’s partner, Louis Aliot and remained a secret up until the eve of the congress. It was also something of a coup for Marine Le Pen, because previously Bannon had focused on her niece, Marion Maréchal Le Pen as the rising star of the French far-right. The latter’s appearance at the CPAC meeting in Washington appeared to signal that she is preparing to come out of her temporary retirement from politics, sensing perhaps that her aunt is running out of steam.

Le Pen doesn’t quite look like she’s finished just yet. There were, of course, dissenting and disappointed voices at Lille: it’s not difficult for a journalist to find a congressiste to express their frustration that nothing seems to be changing. But Le Pen was cheered to the rafters whenever she spoke and Bannon went down a (worrying) storm as he told his audience to wear the accusations of being racists and xenophobes as a ‘badge of honour’ and was greeted by chants of 'On est chez nous'.

The main events on the Sunday were the election of the party president and executive committee and the adoption of new party statutes. Marine Le Pen was easily re-elected, with no challengers and just 2% of spoilt ballots. The election to the party executive was a little disappointing for her, with some of the old guard getting back on, but the key points are that Nicolas Bay and her new best friend, Sébastien Chenu were re-elected too. And, more importantly, her niece did not stand and so has no formal platform within the party, even if she might be planning a comeback before 2022. The next election of the party president is in three-years’ time and the party statutes specify that the head of the party is its candidate for head of state. Le Pen also had the satisfaction of seeing new party statues ratified, which included the abolition of the role of honorary president, i.e. her father.

La cerise sur le gateau, however, was the much-anticipated change of the party name, which had been mooted as early as May last year, after Le Pen’s defeat by Macron and as a means of reaching out to other parties to form an alliance ahead of the general election. Then, one of the suggestions was the Alliance Républicaine et Patriote, but Le Pen lost control of the term ‘patriote’ when Philippot set up his own group within the FN called Les Patriotes and then left to found his own party under that name. Various other options had done the rounds since then, but the lexical field of terms is limited, not just by ideology but also by others having already registered certain terms. Even the ownership of the name Front National was disputed back in the early 1970s and in itself it masked the quite disparate range of microparties that gathered together under the FN umbrella and Jean-Marie Le Pen’s leadership, from hardline Catholic intégristes to the defenders of Algérie Française to the nostalgiques de Vichy and white supremacist groups, or even the rump of French monarchism.

Nevertheless, Marine Le Pen had made it clear in the weeks leading up to the congress that, for her, if the FN is to become a party that can enter into strategic alliances with other parties and hope to govern, it has to change its name. She didn’t quite say that the name Front National has become a toxic brand, but that was her subtext.

Her choice, the Rassemblement National is not without its problems, perfectly well outlined in this article in The Guardian. In the first place, there are historical echoes of a collaborationist party of the 1940s, the Rassemblement National Populaire. In the second place, it’s been used before – by her father in 1986, not for a party but an electoral alliance that reached beyond the narrow confines of the FN. And in the third, according to a number of sources, the title has already been registered.

In itself, the term rassemblement is not problematic. It means assembly, group, union, coming together. Before it morphed into the Front Populaire, the broad left-wing anti-fascist alliance that won the 1936 French general election was known as the Rassemblement Populaire. In more recent times, rassemblement has generally been associated with parties of the Gaullist right. Thus, in 1947 Charles de Gaulle set up the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF) and Jacques Chirac the Rassemblement pour la République (RPR) in 1976. Towards the end of the 1990s, Charles Pasqua, who was active in both the RPF as a young man and in the RPR as its main organiser, quit the RPR over its pro-European stance and set up a Rassemblement pour la France along with fellow Eurosceptic Philippe de Villiers’ Mouvement pour la France and took more seats in the 1999 European elections than the main RPR list, led by Pasqua’s former protégé, Nicolas Sarkozy.

Marine Le Pen herself had already used the word before, in the general and intermediate elections between 2012 and 2017, through her Rassemblement bleu Marine, aimed at establishing a bridgehead to right and far-right politicians and voters alienated by the FN brand.

Although the announcement of a new name was warmly applauded by the congress, it was in itself something of a disappointment. And of course, historians, journalists and politicians jumped on the announcement straightaway. On the Monday morning following the announcement, Igor Kurek, the president of what remains of Pasqua’s RPF, went on national radio to claim that he had patented the title and was in no mood to let Le Pen have it. As time went on, however, it turned out that Kurek had not actually registered the name and had left it to an associate Frédérick Bigrat (no, honestly, I didn’t make that up), whose name appears on the registration and who is, in fact, happy to turn the name over to Le Pen. Meanwhile the revival of the name Rassemblement National exercised a number of French historians, including the excellent, but by his own admission macroniste Jean Garrigues, given its echoes of Vichy and the execrable Marcel Déat. Rather than just a collaborator, Déat was a collaborationist who believed that France should not just put up with German occupation, but fully throw itself into becoming a full-on and unapologetic a fascist state.

Le Pen has left the adoption of the name open to a poll of the membership, to be decided over 'the coming weeks'. But the question is, will a new Rassemblement National appeal to or be able to reach out to other parties on the right? Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, leader of Debout la France, seems willing to open talks, as do the historic but tiny Centre National des Indépendants et Paysans. But the real target is an alliance with Laurent Wauquiez and Les Républicains (LR).

The tentation frontiste is one that has exercised the republican right in France for more than thirty years, but under leaders like Chirac and Philippe Séguin, and even Pasqua the line was clear. No collaboration with the FN. Sarkozy was less forthright, but preferred to combat the threat to his right flank by using the rhetoric of the far-right against it. His success at the 2007 presidential election was built, in part at least, on bringing a large part of the electorate that had voted for Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002 back into the republican fold. By 2012, however, his failure to deliver on promises of immigration choisie and maîtrisée go a long way to explaining the success of Marine Le Pen. At the 2015 regional elections, Sarkozy refused to back Socialist lists better placed than LR ones in run-off elections against the FN, a position that drove a deep wedge between him and Christian Estrosi. And I have outlined in previous blog posts that while Fillon called for his voters to rally to Macron as soon as he knew he had been eliminated from the presidential race on 23 April 2017, Wauquiez’s position was that a vote against Le Pen was not a vote for Macron. Today, there are plenty of voices on the right of LR who think an electoral alliance with the FN/RN is acceptable or even desirable.

The latest of these is one Thierry Mariani, a junior minister under Sarkozy and Fillon. On the eve of the FN congrès de refondation, but in an interview not published until the Sunday in the Journal de dimanche, Mariani, who represented his native Vaucluse in the National Assembly from 1993 to 2010 before becoming transport minister, said that the FN/RN had changed, and that the time has come for the right to abandon its centrist allies and talk to the far-right.

You would be forgiven if you’ve never heard of Mariani. He’s not exactly a household name even in households where these things matter, but his provenance is revealing. Born in Orange, in the Vaucluse, in 1958, he was mayor of the nearby town of Valréas from 1988 to 1995. Elected deputy for department’s fourth constituency (Orange and its environs) in the right-wing landslide in 1993, he held his seat until 2010, when Sarkozy made him a minister (in France, as in the US, you cannot sit in government and parliament). He was also a regional councillor for Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA) from 2004 until 2015.

The Vaucluse is one of the southern heartlands of traditional FN support, built on a strong pieds-noirs presence and throughout his career Mariani has faced the challenge represented by Jacques Bompard, a former member of the far-right wing movement Occident and a founder of the FN in 1972 with Le Pen père. Bompard gained national prominence when he was one of three FN mayors elected in the 1995 municipales, for Orange, a position he still occupies today. Bompard left the FN in 2005, out of frustration at Le Pen’s authoritarian style and, above all, his refusal to take local politics, the bedrock of the French system, seriously. After joining Villiers’ Mouvement pour la France, Bompard left after the MPF fell within the orbit of Sarkozy’s UMP. With regional elections looming in March 2010, Bompard set up his own Ligue du Sud, an alliance of small far-right groups, including the particularly charmless Bloc Identitaire, whose use of the wild boar as a symbol, linking them back to their ancestors the Gauls tells you all you need to know.

In those elections, Bompard lined up against an FN list headed by Jean-Marie Le Pen, a Socialist one led by Michelle Vauzelle, president of the regional assembly since 1998 and… Mariani, heading a majorité présidentielle list. Bompard was eliminated, with less than 3% of the vote and Le Pen, Vauzelle and Mariani went forward into the second round. But it was noticeable throughout the campaign that Mariani focussed entirely on the shortcomings of the ruling left-wing regional administration under Vauzelle and made very few attacks on Le Pen. Vauzelle won and his list’s 44% of the vote in the run-off gave them 72 seats to Mariani with 30 (from 33%) and 21 for the FN (23%). [French regional elections give the winning list half the seats. The remaining half is then allocated proportionally.] There was a sense of relief at UMP headquarters that the right would not have to face the embarrassing situation of an offer from the FN to form a coalition, not least because Mariani was difficult to handle.

In the summer of 2010, Mariani was one of a group of thirty or so deputies who rebelled against what they saw as government backsliding over immigration and security by setting up La Droite populaire, a group of right-wing frondeurs within the UMP. There also appears to have been an issue of a personal offence on the part of Mariani, who felt that he should have been appointed to a ministry already. In fact, the nomination came in the autumn, but the group remained and Mariani was a forthright supporter of the droitisation of Sarkozy’s second round campaign in 2012.

Mariani is, moreover, close to the Kremlin. He is married to a (younger) Russian wife, has visited the Russian occupied Crimea and also is a supporter of Syrian president Bashar-al-Assad. All of which makes him very lepéncompatible when it comes to geopolitics and media support. But there’s a further twist to this story. Regular readers of this blog might recall that I mentioned a new kid on the FN block, Sébastien Chenu, who came to the party from the UMP. According to Le Canard enchaîné (24 January 2018 again), Chenu has been pushing Mariani as a possible tête de liste for the FN/RN for the 2019 European elections…

Since the announcement of the plan to change the name from Front to Rassemblement National, the response from within Les Républicains, Mariani apart, has been muted. Wauquiez has been mired in a scandal of his own recently, after giving a series of lectures at a Lyon school of government where he imagined no-one would record the proceedings and where he slagged off various political figures whilst adopting a very clear identitaire posture. Wauquiez claimed that his provocative and populist approach was no worse than that of a young Jacques Chirac, evoking a time when the former president was known as ‘le bulldozer’. That claim in turn earned him a rebuke from former PM Jean-Pierre Raffarin that reminded me of Lloyd Bentsen’s comment to Dan Quayle during the 1988 vice-presidential debate, when Quayle compared himself to JFK: ‘Senator, you’re no Jack Kennedy’.

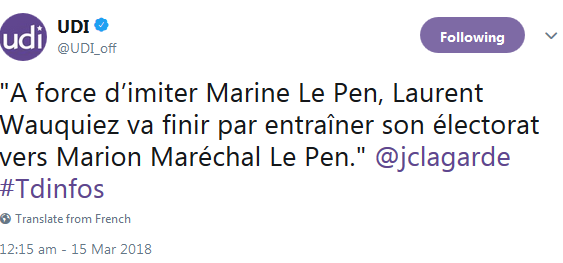

But Mariani has a point. In amongst the froth, he mentioned that he feels the time has come for the right to break once and for all with their former allies in the centre and centre-right. Let them get into bed with Macron and the éternel marais described by Maurice Duverger and revisited in a recent article in Modern and Contemporary France by Robert Elgie. For their part, some on the centre-right are thinking too that Wauquiez’s posturing is leading to a very clear separation that will not end well for Wauquiez, nor Marine Le Pen. The tweet below, from Jean-Christophe Lagarde, president of the Union des Démocrates et Indépendants is unequivocal. 'By imitating Marine Le Pen, Laurent Wauquiez will end up dragging his electorate towards Marion Maréchal Le Pen.'

Elsewhere, there is a feeling that Marine Le Pen has played her trump card (no pun intended) and that it has fallen flat, though that comes from Le Figaro, the LR’s daily newspaper, so it might be wishful thinking.

Emmanuel Macron wishes everyone a Happy New Year

Read MoreLaurent Wauquiez's crushing victory still leaves questions unanswered

Read More