Green shoots - la vague verte in France's municipal elections

Let’s be clear about this. The performance of Europe Ecologie-Les Verts (EELV) in this year’s French municipal elections is historic. Yes, we have seen them perform well before, usually in European elections (1989, 2009, 2019). Hitherto, at the local level their success has been limited. There have been a few communes where the ecologists have taken control (Noël Mamère in Bègles in the Gironde was a stand-out), but they have generally and historically been the junior partner in alliances with other parties of the left - most prominently the Parti Socialiste (PS) in Paris or Lille, and an array of other left-wing parties and micropartis in others. But they have hardly ever been in the dominant position and able to impose their tête de liste and take the mairies of France’s larger cities. Before last Sunday, only Grenoble had a Green mayor, Eric Piolle, who thumped the PS in 2014. According to Le Monde, the Ecologists now administer 20 towns and cities with a total population of over 2 million administrés. Lyon, Bordeaux, Grenoble, and Strasbourg are considerable victories.

Figure 1 - Eric Piolle, mayor of Grenoble since 2014, checks the 2020 results in the local paper whilst enjoying a grand crème and a croissant, and trying not to look too smug…

Piolle’s victory in 2014 now begins to look like an outlier for 2020, and to some extent it is. But let’s go back a stage. Readers with longer memories will recall the time of the gauche plurielle, a rainbow coalition of the PS, Les Verts, the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) and various other left-wing groups that governed France from 1997 to 2002 under the leadership of Socialist PM Lionel Jospin. Within that alliance, the PS were very definitely the dominant partner, with both the Greens and the PCF (a party in apparently inexorable electoral decline since the 1980s) the juniors and the other parties, such as the Mouvement des Citoyens (MDC), more like political clubs gathered around one or two prominent political figures. (The MDC was to all intents and purposes the Jean-Pierre Chevènement Fan Club.) The 2002 presidential campaign blew the gauche plurielle apart, although the PS recovered surprisingly rapidly, winning all the intermediate elections between 2002 and 2007 until it then lost the imperdable presidential election of 2007.

Two years later, the PS and the Greens ran separate lists at the 2009 European elections and both polled the same nationwide score, 16%. A year later, Les Verts fused with other left-wing ecologist groups to form EELV and, in the form of the high-profile broadcaster and environmental campaigner Nicolas Hulot, seemed to have the perfect candidate for the 2012 presidential election. Except the movement chose Eva Joly in their primary and she failed to make much of a dent, winning less than 4% of the vote. Nevertheless, François Hollande, impressed by the Greens performance in 2009 struck a series of local agreements for the 2012 legislative elections that followed his victory over Nicolas Sarkozy, guaranteeing the Greens seats in the National Assembly and all looked to be fair set for a PS administration with EELV covering their environmentalist flank. To that end, the EELV general secretary Cécile Duflot became minister for local government under PM Jean-Marc Ayrault.

Figure 2 - Summer 2011 and EELV leaders celebrate the nomination of Eva Joly (in the red glasses) as their candidate for the forthcoming presidential election. To the right of her is Cécile Duflot and immediately behind Joly, in profile, is Yannick Jadot.

It was not very long, however, before the realities of governing versus an electoral alliance became all to evident. The party’s deputies and senators split over their future relationship with the Hollande administration and Duflot quit the government in March 2014. Other than disagreements over policy, Duflot and many within EELV found that the PS still took a deeply condescending attitude towards them as junior partners and this was only exacerbated in the 2014 municipal elections. That said, local agreements still bound them to the PS and helped the left to hold on to Paris, Lyon and Lille. Grenoble, however, was another matter altogether.

The capital of the Dauphiné has very specific problems with pollution, caused by its geographic location. Briefly, the city sits in a bowl surrounded by moutains and in certain conditions, pollution has nowhere to go. Grenoble had been under the administration of the Socialist Michel Destot since 1995. For the 2008 municipal elections, Destot opted to ally himself with the moderate centre and centre-right and although his strategy helped him retain city hall, the Greens, then led by Maryvonne Boileau, took 15% of the vote in the first round and 22% in the second. Already, then, the stage was set for Eric Piolle to force his way further into the breach in 2014. Leading with 29% of the first round vote, a quadrangulaire, four-way run-off saw him finish first with 40% in the second, ahead of the PS list on 27%, the UMP on 23% and the FN list with a little under 9% (dropping from 13% in the first). Piolle had won not just without but against the Socialists.

The lesson of Grenoble in 2014 was instructive, but 2017 played an important role in transforming the relationship between EELV and the PS. If the Hollande presidency was not destructive enough for the Socialists, the election of Benoît Hamon as their candidate to succeed him was catastrophic. EELV’s choice of Yannick Jadot was hardly better. Just as everyone had expected Hulot to be chosen for 2012, so Duflot was the favourite, but she was comfortably beaten by Jadot it what seemed to the general public as just perverse. Then, Hamon opened negotiations for a broad left candidature with Jadot and Jean-Luc Mélenchon, which the former accepted and the latter refused. Hamon was crushed and the PS left in ruins. But it was a chastening experience.

Figure 3 - Best friends forever - Hamon and Jadot seal their alliance in 2017

Wind the tape forward to 2019 and EELV, led once more by Jadot after a brief flirtation with Hamon’s Génération.s movement, were the surprise package of the European elections, with 13.5% of the national vote putting them third behind the Rassemblement National (RN - 23%) and La République en Marche (LREM - 22%), but ahead of Les Républicains (LR - 8.5%) by some distance. More significantly Jadot’s score outstripped the combined totals for the PS-backed list and also Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (LFI), both of which scored a shade over 6%. As I said at the top of this piece, we have seen this sort of thing before. What is new is that the particular conjoncture in French politics at the moment gave EELV the whip hand in negotiations with its partners on the left going into the local elections. They were the glue binding together a raft of different electoral alliances. But while EELV brought the voters, the PS provided the foot soldiers.

The vague verte is really a vague rose-verte. In Bordeaux, Lyon, Besançon, Tours, and Marseille, the Greens have succeeded in a variety of rainbow alliances. By the same token, the Socialist victories in Paris, Nantes, Rennes, Clermont-Ferrand, Nancy and Montpellier (among others) have been thanks to the support of EELV. Grenoble, Strasbourg, and Poitiers stand out as towns where the Greens saw off the Socialists in the second round, while in Lille, Martine Aubry (PS) defeated EELV by fewer than 300 votes.

Figure 4 - Bordeaux on 28 June 2020. Pierre Hurmic’s Bordeaux Respire! list ended the right’s domination of city hall since 1945.

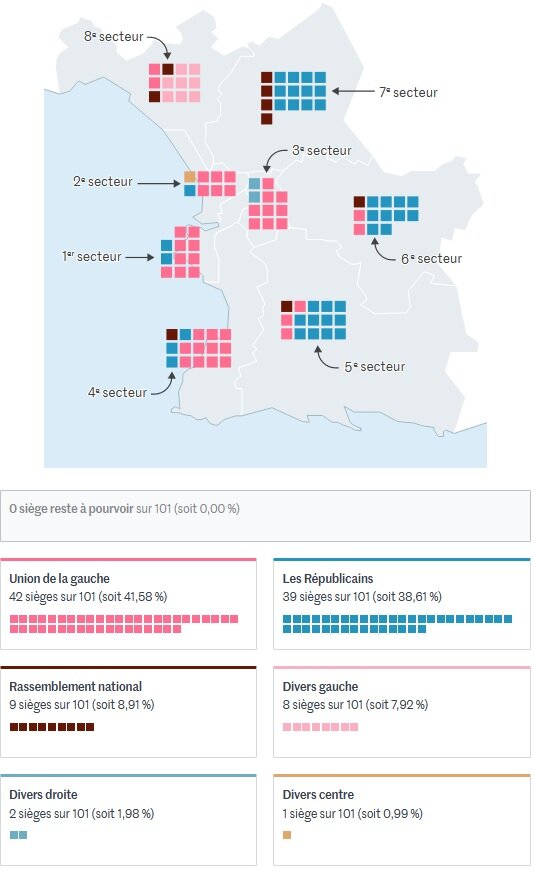

At the time of writing, the future of Marseille remains in the balance. Although Michèle Rubirola’s broad left alliance Printemps Marseillais took most votes, the division of the city into electoral districts means that, unlike the situation in Paris and Lyon, where the results are a foregone conclusion, it is not certain that she will win the ‘third round’ and be elected mayor when the city council delegates meet.

Figure 5 - L’union fait la force. From left to right: Julien Bayou, national secretary of EELV, Michèle Rubirola, mayoral candidate of the Printemps Marseillais alliance, Olivier Faure, first secretary of the PS and Socialist Benoît Payan on the campaign trail in the cité phocéenne

Figure 6 - ‘Largement en tête’, but not certain of taking overall control of the hôtel de ville.

As the Figure 7 below from Le Monde shows, the future of Marseille remains in the balance. (I will come back to the situation in Paris, Lyon and Marseille in a later post.)

Figure 7 - All still to play for in Marseille - from Le Monde

How, then, do we explain this success? It’s not difficult to see why environmentalism is making its mark, but the social and political conjuncture has assisted enormously. The success of EELV is essentially in large cities of more than 100,000 inhabitants. There are very few exceptions to this rule, but Poitiers - for years a Socialist bastion - stands out. There is considerable evidence to suggest that the EELV-PS alliance has brought back to the left those centre-left voters who supported Emmanuel Macron in 2017. And one has to wonder whether Macron did not make a huge tactical error - or finally declared his hand - by jumping into alliances with LR against the Greens and stigmatising them as the dangerous radicals that they are not. These are all part of the explanation - there is not one sole reason. One can also add into the mix the term dégagisme, a desire to ‘get rid’ of the old figures and bring in new blood - a phenomenon that Macron himself benefitted from in 2017 after all. So, if you bring in the environmental concerns of EELV and the ‘embededness’ or maillage of the PS at the local level, this is what you get. It is also worth noting, as Le Monde has, that EELV lists have been successful where the outgoing mayor was not standing for re-election.

It is not the whole story of course and there is more to tell in the days to come. But this will do for now.

A suivre